-

Constantin Antonovici, Romanian Tradition, circa 1950s

Constantin Antonovici, Romanian Tradition, circa 1950s -

Constantin Antonovici, Head of Brancusi V, 1956

Constantin Antonovici, Head of Brancusi V, 1956 -

Constantin Antonovici, Head of Brancusi, 1957

Constantin Antonovici, Head of Brancusi, 1957 -

Constantin Antonovici, Modern Head, 1953

Constantin Antonovici, Modern Head, 1953

-

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View

-

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View -

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View -

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View -

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View -

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View -

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View -

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View -

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View -

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View -

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View -

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View

Constantin Antonovici: Mythical Modernism | Installation View

WESTWOOD GALLERY NYC was pleased to present Mythical Modernism, a retrospective of Romanian-born sculptor Constantin Antonovici (1911-2002), curated by James Cavello. The exhibition featured fourteen sculptures, 1942-1975 (marble, metal, wood) and never-before-seen ephemera from the Antonovici Archive highlighting a life dedicated to art. This exhibition was one of a series of rediscovered artist estates, as part of the gallery core program, and is in collaboration with Gallery: Gertrude Stein, a historic contemporary NYC art gallery.

Antonovici established himself as an artist in the 1930s while still a student at the Fine Arts Academy in Iaşi, Romania. His skill as a wood artisan was recognized in sculpture competitions and he received commissions to carve altars for two of the local churches. The turmoil of the war in the 1940s changed the scope of his work, away from traditional into innovative forms nurtured from nature. From the 1950s, Antonovici developed into a post-synchronistic, modernist sculptor, constantly influenced by his upbringing in Neamţ, Romania, a countryside area known for having the most monasteries in the world, per square kilometer.

His sculptures are refined forms, reduced to their essential attributes, and are anchored both in mythical folklore and the tradition of Modernity. In 1967, Alain Bousquet wrote about Antonovici in an article in Albert Camus’ newspaper, Le Combat: “Constantin Antonovici offers a rare example of sobriety and perfection, for that inner force similar to music.” Bousquet placed Antonovici in the context of surrealism and cubism and compared him with Jean Arp and Giacometti. Antonovici’s totemic figure was the owl, whose imagery and symbology preoccupied him from childhood. With the owl’s fundamental verticality and sentinel view, the bird was an important motif representing strength and wisdom as a mythological creature. “It lies at the base of my inspiration and traces my way in modern art.” For over thirty years Antonovici explored the complexity of the owl with several sculptures on view in the exhibition. Included is one of his earliest bronze owl sculptures dated 1942 with recognizable features, in comparison with a regal monolithic marble owl dated 1975, with only the eyes and sleek shape as a recognizable form. The sculptures are documented in the 1976 book, “Constantin Antonovici: Sculptor of Owls."

Two works entitled “Head of Brâncuşi” (1956) reflect Antonovici’s homage to the Maestro in modernist form, and other bronze sculptures, “Mephistopheles” (1949) and “Portrait” (1953) are indicative of the purity of modernism, which Antonovici refused as ‘abstraction’. Several sculptures are exhibited on original pedestals of carved or constructed wood and show the influence of Romanian ethnography from the Carpathian Mountain region.

The exhibition is curated with ephemera from the artist’s archive to provide a deeper view of the artist as he tried to find his presence in the New York art world, and at times barely surviving. The archive includes letters about his participation in anti-communist protests in the 1960s, his role in the trial of revealing Bishop Valerian Trifa as a former Nazi, a letter from Richard Nixon accepting a bust of Dwight D. Eisenhower created by Antonovici in gratitude for his immigration to the U.S., correspondence with collector David Kreeger, as well as vintage photographs of artworks in the studio. Also on exhibit is Antonovici’s typewritten personal account “How I Knew the Great Brâncuşi” from 1951, as well as a rare recommendation certificate written by Brâncuşi to confirm Antonovici’s talent as an artist. Also included are letters at the culmination of the artist’s life which portray a long health battle due to a stroke, and ongoing eviction proceedings in the artist’s rent-controlled NYC apartment.

From Antonovici’s history, a defining time in his life was his seven-year challenging quest from 1940-47, surviving war and imprisonment, to meet the great Constantin Brâncuşi who lived in Paris. In 1940 Antonovici worked in the studio of the famous sculptor Ivan Meštrovič in Zagreb (Croatia) for six months. After returning to Zagreb from a brief trip to Romania to defer draft, he found Meštrovič had been imprisoned. Antonovici ended up being arrested by the German SS, sent to Belgrade and later imprisoned in Germany for his refusal to fight on the side of the Nazis. At the brink of death, a doctor in the prison helped get him a guarded release to Vienna where he was allowed to attend the Academy of Fine Arts, and studied with Professor Fritz Behn, who made him a teaching assistant. Antonovici later studied woodcarving techniques in Tirol (1945-47) and then relocated to Paris where he met Brâncuşi.

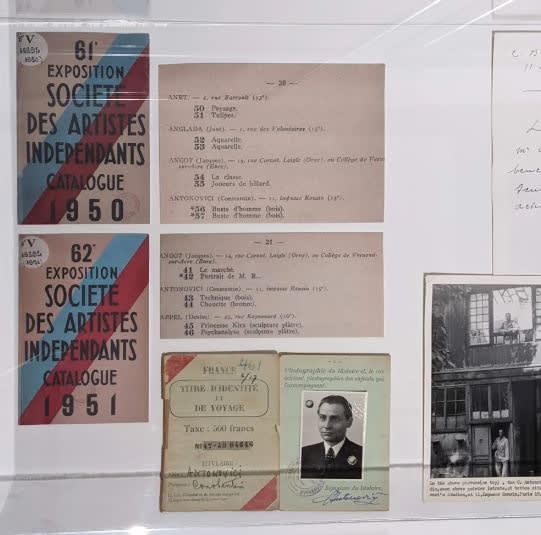

Brâncuşi, who was not necessarily amenable to meeting another young artist, ended up accepting Antonovici as a studio assistant from 1947-1951. Working in Brâncuşi’s studio at 11 Impasse Ronsin changed Antonovici’s outlook on life and art and he was also fortunate to continue making his own sculptures during the four-year period. In 1950 and 1951 Antonovici was invited to participate in the prestigious Salon des Indépendants at the Grand Palais in Paris, along with artists at the forefront of avant-garde art movements; in both years at the Salon Antonovici exhibited two sculptures including an Owl bronze and listed his address as 11 Impasse Ronsin, the same address as Brâncuşi.

Brâncuşi required no less than perfection in craftsmanship from any artist honored to work in his studio, and Antonovici proved worthy to the Maestro. They also shared a bond due to commonalities in their peasant upbringing in Romania and their mystical view of nature related to folklore. Brâncuşi taught Antonovici how to forge and make tools for sculpting, which were better and longer lasting than any store-bought tools. Antonovici wrote about Brâncuşi: “He creates like a God. He commands like a King. He works like a slave.” Brâncuşi gave Antonovici a hand-written statement to endorse Antonovici’s artistic talent and relentless work ethic.

-

Constantin Antonovici, a sculptor on two continents

Magdelena Popa Buluc, Cotidianul, 23 Dec 2021 -

Mythical Modernism, Retrospective of the Romanian-born sculptor Constantin Antonovici

Magdalena Popa Buluc , Jurnalul, 8 Nov 2021 -

Romanian sculptor, disciple of Brâncuși, exhibited in New York

Ruxandra Hurezean, Sinteza, 8 Nov 2021 -

Constantin Antonovici (1911-2002), Romanian Sculptor at Westwood Gallery NYC

Cosmin Nasui, Modernism, 4 Nov 2021